I’ve written before about the trials and tribulations of making aliyah — and the ways in which I think Israel’s culture is similar to Ireland’s and differs from it.

One of the benefits of staying in Israel long enough to be considered an oleh hadash-that-isn’t-so-hadash is getting past the “where did you come from and why did you move to Israel?” routine that prefaces meeting new people here.

Having gone through the following enough times to last a lifeline (over the course of five years, I add), here’s a template FAQ to which I will be referring future inquisitors.

***

Person at Shabbat table: You have an accent! Where are you from?

Me: That’s a Nachlaot accent. Didn’t you know?

Person at Shabbat table: I mean, where did you live before Nachlaot?

Me: Rechavia.

Person at Shabbat table: OK, where are you originally from?

Me: I was born in a hospital.

Person at Shabbat table: In what country was that hospital located?

Me: Western Europe

Person at Shabbat table: Oh, you’re from London! Do you know Harry Cohen? How about Rivka Solomons? Have you visited Golders Green?

Me: (Reluctantly) No, I’m from Ireland.

—Interjection: Israelis and olim alike very seldom meet people from Ireland and assume that all English speaking olim are, by default, from the US. So, to fend off a puzzled “Eer-land?!” I sometimes need to add, for emphasis, “Guinness!” “Riverdance! ” “Michael Flatley!”—

Person at Shabbat table: Oh, you’re from Ireland! I’ve never met a Jew from Ireland! Are there many Jews in Ireland? (Why is it that people always ask these two questions in this exact succession?)

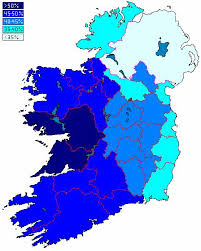

Me: It’s a very small community. There are about 2,500 Jews in the country, mostly in Dublin. I grew up in Cork, in the south of the country.

***

Once the above routine has run its course I try to change subject as quickly as possible.

Irish people’s go-to for this purpose is always the weather — but in a country with as stable as predictable a climate as Israel that doesn’t help much.

But there are things like:

That’s great chicken soup, X, where did you get the recipe from?

My discomfort with talking about growing up in Ireland is definitely palpable and I’m sure that it has given more than one person pause for worry about my sanity. So why do I hate talking about it so much?

For one, I’ve had this conversation about a thousand times. I have more to say about it than would be appropriate for friendly small talk with somebody I’ve just met (see: below). And, perhaps most significantly, because I moved to Israel, in large part, precisely to avoid this conversation — to become part of the mainstream.

So — for one time only — let me open up a bit about it and give the subject a good airing.

Growing up Jewish in Ireland

I was born in Dublin, Ireland’s capital, to a Jewish mother and a Catholic father.

Growing up, we lived overseas for a few years: in Aberdeen, Scotland and in The Hague in The Netherlands (my late father worked for Halliburton and the moves were job-related).

After a few years in the UK, we returned to Cork, Ireland’s second city, where my mother is from. My late maternal grandparents lived in the city about twenty minutes’ drive from our house too — so we were very close to them growing up.

It took me a while to even realize that I was Jewish — that I was somehow different from my friends and just about everybody except my immediate family members.

In fact, my first memories after moving back to Cork have nothing to do with religion at all.

I have fond memories of making Lego movies with my friend and going through a phase of being obsessive about working out in the gym. The latter seems to have passed (sadly).

Gradually, the feeling that I was different — which is why, in effect, I don’t like talking about this — crept up on me. Slowly, insipidly at first, I began to feel like a fish out of water.

That — for those looking for the TL;DR to this — is really how I would define my experience of being an Irish Jew: Of being extremely uncomfortable with the exceptionalism of those dual and seemingly conflicting identities. And of being very conscious of not quite fitting squarely into either bracket.

Part of the reason I don’t like being wheeled out as the Irish Jew party trick, or being quizzed about my background, is because it makes me feel like an imposter. Because in truth, I’ve never felt authentically Irish. Or believed that I was perceived as such by my compatriots. In equal measure, it’s also just an uncomfortable topic — and not all the memories which being reminded of my Irish-Jewish identity bring back are good ones.

It’s unsurprising, I guess, that my first memories of realizing that I was Jewish were through the lens of being aware that I was different than the mainstream — the outsider, the odd one out.

Receiving exemptions from religious education in primary and secondary school. Not really knowing what to do with my hands — or my eyes — when The Angelus or The Lord’s Prayer came through the school intercom system twice a day.

Bringing chicken sausages, in lieu of pork ones, to my primary school’s barbecue. And being asked how on earth chicken can be put into sausages (the same way pork can?).

Cork’s Jewish community, throughout the time I lived there but particularly before I left for Israel, was vanishingly small.

My grandfather, the late Fred Rosehill, effectively served as the tiny congregation’s leader. This video (I make a cameo appearance — and have a better barber now) does a nice job at explaining the community’s origins, its history, and its slow demise.

The permanent community — at the ‘height’ I remember, at least — consisted of perhaps a dozen individuals, to offer a generous estimate.

The community’s ranks were swelled—usually temporarily, although occasionally not—by Israeli expats. They typically moved to Cork to work in one of the international companies dotted throughout the city. Many were not religiously inclined and interested in affiliating themselves with the tiny local Jewish community. Besides the very few that took up permanent residence in Cork, those that joined our ranks inevitably left when they returned to Israel — or elsewhere.

Gradually — as individuals died, disassociated from the community, or moved to Israel (or further afield) — the tiny numbers that it consisted of slumped even further.

To the point (which stretches as far back as I can remember) that assembling a minyan was a heroic initiative that would require congregants travelling from adjoining counties for some special purpose. For High Holidays, Chabad trainee rabbis were “imported” from the UK to ensure a minyan (quorom) throughout the day. They reported drawing bewildered looks — and occasionally teasing leers — as they traveled through the city.

There were no regular services during my involvement with the Cork shul except for a Shabbat service that was held once a month. My bar mitzvah was the first to be held at the shul in a long time.

Growing up, I spent a considerable amount of time with my late grandfather. Were it not for his influence and determination to keep the community going despite its small numbers, and the internet, I’m not sure that I would have had a strong enough Jewish identity to prioritize moving to a community where Judaism was practicable.

The Shul That Became A Museum

Growing up, I spent a large amount of time helping my grandfather to give tours of the synagogue to school groups. And to take care of the many unglamorous activities that go into maintaining even a small Jewish community function (my late grandpa was a stickler for making sure that the community email newsletter list was always kept well updated!).

Countless schools and museum groups visited the shul on South Terrace which was later deconsecrated and is no longer in use. At other times, these were visiting Jewish groups from the US who stopped off in Cork during a cruise itinerary.

One thought kept creeping up on me, but more so after my first trip to Israel, was that the shul was seeing more use as a museum than it was as a place of religious worship. And Judaism doesn’t belong in a history book.

However, the real impetus to start looking for places to emigrate to was attending a Birthright trip to Israel when I was 16 or so.

A Chabad rabbi in Ireland — Rabbi Zalman Lent, who now serves as Rabbi at the Dublin Hebrew Congregation — got in touch as he was leading a group from Ireland on a Birthright trip to Israel. (At least, this is how I remember events).

At this time, my only exposure to Judaism, besides helping out at the shul, was through listening to podcasts (Chabad.org’s audio catalog, and then the wonderful Rabbi Eli Mansour, were my go-tos).

I attended Presentation Brothers College (PBC) — a local high school run by an order of Brothers. Growing up, I didn’t have a single Jewish friend. This was due to demographic reasons rather than by choice: There were possibly two Jewish kids my age in the entire city and county and neither went to my school. At the time I attended, I was the only Jewish pupil in the high school which had more than 500 pupils.

Besides Cork, the only Judaism I was familiar with — from visits to family members abroad — was that of the diaspora (the UK, the US, and Israel are where most former Cork Jews have moved to). There, as far as I could observe, Jews lived in close-knit communities, often attended separate high schools, and seemed to keep close to, but at a slight difference from, the societies that surrounded them.

Ultimately, what I perceived to be a somewhat closeted existence appealed to me about as much as staying in Cork with its almost total dearth of Jews and the institutions needed to live an observant Jewish life (it probably goes without saying, but I should point out that there was no source of kosher meat either).

My first trip to Israel opened my eyes to a different possible way of life which both afforded the ability to live a fulfilled Jewish existence but which didn’t require choosing one’s city or social circle based on their religion. (If you see Judaism as an ethnicity as well as a religion this isn’t as self-contradictory as it might at first seem!)

It was a place where, unlike Cork, I wouldn’t be a minuscule minority — where I was part of a community that was now a mostly historical artifact that evoked the occasional attention of the media and scholars as well as the reluctant interest of bored high school students who chose Judaism as one of their focuses for their Religious Studies exam.

As the world’s only Jewish majority country — the one in which Judaism began — Israel also offered something which the diaspora, in its entirety, simply couldn’t.

A place where being Jewish was the norm. Where the things needed to live a fulfilled Jewish life, including religious holidays, were baked into the country’s very DNA. And a society in which keeping kosher didn’t mean having to choose between three obscure restaurants in whatever neighborhood the city’s Jewish community deemed best most suited to establish a center for itself.

On the linear scale of the Jewish world, Israel was the polar opposite of Ireland.

I was sold.

Staying in Cork

I don’t believe in dwelling on regrets, But if I had to list one of my biggest ones so far, it was probably staying in Cork for university (as well as studying something I wasn’t passionate about — for another post, or better none at all).

The passing of my late father, right before I started my law degree, had a lot to do with that. I had looked into studying in New York, the UK, and Israel (and received offers). But I ultimately chose to attend my local university and live at home (regret number two; Take it fro me: you don’t want to be learning how to iron your clothes during ulpan!).

At this stage, my consciousness had been fully awoken to being Jewish — I was now teaching myself ktav Rashi to be able to learn the Talmud. But also to the fact that Israel was rather despised in the country I lived in.

Through my trips to Israel and the continued inspiration of Rabbi Mansour’s wonderful and passionate audio shiurim, I was also beginning to take religious observation more seriously in a city and college campus that was almost devoid of Jewish life.

To move closer to keeping kosher for instance I adopted a vegetarian and then pescetarian diet. But I found the diet constricting. Besides, having to keep quiet about my growing observance felt a bit too much like being a Marrano in Inquisition-era Spain.

As I entered university, I couldn’t help but notice that merely mentioning Israel in conversation felt akin to walking around campus with a megaphone and cursing one’s lecturers. This is a battle and feeling that is probably familiar to many American readers. But there was something about facing this feeling almost alone that felt particularly isolating.

***

Is There Really No Anti-Semitism in Ireland?

When people ask what growing up Jewish was like in Ireland, they often next want to know whether I encountered anti-Semitism during my 20 or so years living in the country.

The party line of Irish Jews since time immemorial has been that the country is almost totally devoid of anti-Semitism and that Ireland has an exemplary and unique track record in being almost totally untinged by anti-Semitism.

To the extent that — save the Limerick Pogrom — there haven’t been any mass waves of overt anti-Semitism in the country those making that assertion are correct.

But internally — and here publicly — I have always both contested that narrative and felt that several historical facts (such as Jews’ exclusion from certain social clubs to name one) flatly contradicted that claim.

Growing up, I have memories of us, and my grandfather, receiving anonymous anti-Semitic phone calls and voicemails. As uncommon as these incidents were, they did happen. Repeatedly — and particularly when the Israeli-Arab conflict was at its most restive.

When I wound up the student news website that I founded and edited at the local university, its Wikipedia page was defaced with a comment alleging that the “chief Jew” deleted the page “in a hissy fit”. (On the second part, the poster wasn’t wrong — I pulled the plug on the site rashly).

This unnerved me more than direct name-calling. Tracing the IP, I could see that it came from somewhere on the college campus. Despite my best efforts to keep a very low profile about my Jewishness, somebody knew who I was, that I was Jewish, and evidently didn’t like that fact. The hardest abuse to take can be that which is cloaked in anonymity.

Other experiences that I remember as deeply uncomfortable were more direct.

There was, for instance, the English teacher who would frequently begin classes on literature by lecturing the class about how “the Jews” were stealing Palestinian land. Sitting a meter from the teacher, I maintained a fixated stare on my desk.

In general, and despite the above (which represent exceptions rather than the norm), I believe that Irish society is tolerant and respectful towards its minorities, including Jews. But equally, I cannot say that I never experienced anti-Semitism while living in the country.

More than that, though, I always felt profoundly uncomfortable — and, I’m sorry to say, embarrassed — about being Jewish in Ireland.

Although globalization is fast changing things, many Irish people only know about Jews and Judaism from American media.

Commonly, after mentioning that I was Jewish, my interlocutor would assume that I was joking. Before realizing that I was not and being hushed into embarrassed silence.

I was acutely aware of the fact that I was and am likely the first and only Jew that many of my friends had met outside of the context of popular culture.

If my experiences seem exaggerated or imaginary, then I encourage anybody reading this to read the comments section on any story about Israel on Irish news websites.

While it’s easy to dismiss those commenting on news websites as a fringe but vocal minority (another party line), to watch many anti-Semitic canards enjoying open and popular support was and remains highly disconcerting for me.

The Jews control the media; Israel is built on stolen land; what the Jews are doing to the Palestinians is worse than the Nazis. Statements like these slip into Irish conversations about Israel, whether in radio chat shows or on online fora — and opposition is thin on the ground.

The distinguishing feature of Irish opposition to Israel and its championing of the Palestinian cause is its often ferocious virulence.

To fail to ascribe anti-Semitic motives to at least a portion of this tidal wave of hate — or to claim that there is no anti-Semitism in Ireland at all — is, in my opinion, to be willfully disingenuous.

Why I Left Ireland

The above probably makes clear why I ultimately left Ireland and came on the crazy journey called aliyah. In doing so, it may also leave the false impression that I deeply dislike the country of my birth — which is very far from the case.

I enjoyed living in Ireland even if — from a Jewish perspective — it caused me to feel increasingly alienated from the country whose passport I held and ill at ease with my own identity as an Irish Jew.

And if this sense of discomfort began at a slow simmer, then it reached boiling point when I began to identify with the Zionist cause — and sensed that virtually all of society held that movement, and often the existence of the State of Israel, to be anathema to their moral code.

Most pragmatically, I couldn’t think of a way to marry within the faith — something which I achieved by moving to Israel!. I also couldn’t envision a long term future in a country where it felt like there was an obvious and sometimes painful dissonance between the passport I held and my religion. Nor one in which merely mentioning the word ‘Israel’ felt like breaking a societal bamboo —which left my options as either to join my voice as a Jewish one in opposition to the country or wage a futile war to challenge mistruths and distortions through hasbara (I delved in that world and — as I recently wrote here — I don’t think that most hasbara is constructive or a good use of time). And finally, simple truth be told, I couldn’t stomach more fish and lentils.

Being Jewish in Ireland was slightly weird. Slightly embarrassing and uncomfortable (for me, perhaps also for others). And something which I usually felt everybody would prefer was just skipped over in conversation whenever it cropped up. For me, and as my own sense of Jewishness and self matured, that simply wasn’t a paradigm that was compatible with being proud about who I was.

My emigration push factor was simply that I felt uncomfortable — at times profoundly so — with being Jewish there.

The countervailing pull factor was that Israel offered a unique selling proposition which no other Jewish community in the world could equal: somewhere where being Jewish was the norm rather than the exception.

For the record, while comparing my experiences in these two countries, there are aspects of Ireland that I far prefer to Israel. Let me end this blog post by listing them.

For one, I think that Ireland has a warm and accepting culture — one which is largely free of the unbridled aggression that sadly seems to be endemic in much of Israeli society.

Like Israel, Ireland punches above its weight internationally — both in terms of the success of its diaspora population and its prominence on the international stage.

Israel, like Ireland, has a relatively thriving tech scene — and one which, like Israel, is focused internationally.

Shitat mazliach and freier culture thankfully doesn’t have a grip on Irish society as it does here. Where Israelis value being often abrasively direct, the Irish value being friendly (if sometimes only outwardly) and congenial. In truth, I’ve come to believe that both approaches have merit. Manners are treating others with consideration are highly emphasized virtues in Irish culture — in Israel, all too often, the former is regarded as a waste of time and words.

Despite all the above, and my sense of feeling proud of where I came from, I couldn’t envision a future staying in Ireland.

I was tired of feeling slightly ashamed and embarrassed about who I was: Always the odd one out, the slightly embarrassed (and perhaps embarrassing) exception to the Irish Catholic stereotype. Kyle from South Park (except in real life).

Feeling comfortable in my own skin — and figuring out who I am (not quite Irish, not quite Israeli — perhaps just a person figuring out his place in the world?) is a slow process of reawakening that is still going on to this day. Even as I write this.

Ireland was, all things considered, kind to me and my family — who arrived there in the late nineteenth century (like most Cork Jews) fleeing religious persecution and forced conscription in Lithuania.

I still have family in Ireland, do business with clients in the country, and am proud to hold an Irish passport (and to fly its flag on my roof).

But — as the long history of the Jewish diaspora bears out, a legacy of nomadic wandering which I believe only the founding of a Jewish state could interrupt — I, by moving to Israel, have broken a chain of living in the country that only stretches back three generations. And that, in a nutshell, is partially why I believe that Israel must exist.

Jews have shuffled between countries since the time they went into exile — facing periodic persecution and expulsions. Sometimes, the road has taken them to common destinations like New York or London. Sometimes to off the beaten track places like Cork. The only place I can see us having sticking power as a people, and being comfortable in our collective skin, is where it all began — here in Israel.

And that — in much more detail than I typically volunteer at a Shabbat meal — is why I made aliyah.